December 2009

Member Editorial

Miniatures Go Three Dimensional

Part II Written By CDHM Artisan

Carolyn Kraft

Part I of our series, we learned that the word miniature had nothing to do with something small, but was instead derived from the Latin word minium, the name of the red lead commonly used to paint pictures. Eventually the word evolved to include anything small. But what's in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet. That which we call a miniature by any other name would be as small. (Thank you, Shakespeare.)

Though the word miniature derived from something flat, when did those precious treasures jump off the papyrus, the canvas, or even the rock and into the hands of a wondrous child (or adult)? Historians claim it happened 400 years ago in Germany with the advent of the first dollhouse. Why then? Why there? Before that time, did people ever have the inclination to reproduce something they had, or wanted, in a smaller version?

The Egyptians did.

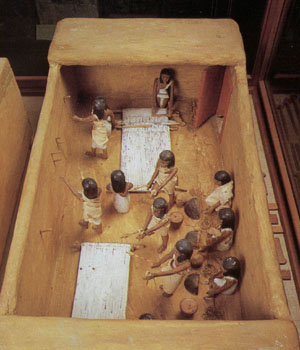

A long time ago (4000 years), in a country far, far away (Egypt) there lived a man named Meketre, Chancellor of Thebes. As a person of wealth, it was imperative that Meketre duplicate the bountiful existence he held in life in order to ensure its continuation after death. For his tomb, Meketre chose a spot in the rocks overlooking the future tomb of his King. Ancient grave robbers vandalized the tomb and stole Meketre's mummy, but they missed something. In 1920, the Metropolitan Museum of Art Excavation Team was clearing the rubble of the collapsing rock in order to map the tomb. Just before the end of the day a worker noticed small bits of stone falling into a crevice between the wall and the floor. Grabbing a flashlight, Herbert Winlock, Chief Investigator, peered into the gap to see "one of the most astonishing sights it is a digger's luck to see…. I was gazing down into the midst of a

myriad of brightly painted little men going this way and that. Little men with sticks in their upraised hands drove spotted oxen; rowers tugged at their oars in a fleet of boats." Meketre had provided for the sustenance he would need in the afterlife by burying with him a miniature copy of his estate: villas, boats, stables, a slaughterhouse, a granary, workshops, a kitchen, a garden, and more. For almost 4000 years, Meketre's life in the hereafter was ensured by his stash of twenty four very detailed and finely crafted miniature roomboxes! These models would magically, and conveniently, become full size in the afterlife.

The practice of being buried with miniature versions of daily life was relatively new to the burial scene of ancient Egypt. Not long before Meketre's time, the nobility began to amass great wealth, which was consequently mirrored by their tombs. Sometime around 2200 BC, painted scenes on tomb walls were replaced by miniature models placed around the coffin. A few hundred years later entire miniature rooms, or tomb boxes, if you will, were given their own chamber in the tomb. It is to history's benefit that Meketre's designer wisely hid the chamber, protecting from grave robbers some of the best preserved artifacts from ancient Egypt.

The practice of being buried with miniature versions of daily life was relatively new to the burial scene of ancient Egypt. Not long before Meketre's time, the nobility began to amass great wealth, which was consequently mirrored by their tombs. Sometime around 2200 BC, painted scenes on tomb walls were replaced by miniature models placed around the coffin. A few hundred years later entire miniature rooms, or tomb boxes, if you will, were given their own chamber in the tomb. It is to history's benefit that Meketre's designer wisely hid the chamber, protecting from grave robbers some of the best preserved artifacts from ancient Egypt.

One might not consider a miniature room model for the dead in the same category as today's miniatures, although you can bet the artisans who created them 4000 years ago would loved to have brought them home for their children, or to display in their homes, instead of burying them with a dead guy. Those tomb boxes (which interestingly enough rhymes with roomboxes) required "a meticulous approach to detail and a great deal of patience on the part of the artist", just as the miniature paintings before them.

It is highly doubtful that Meketre and his contemporaries thought to make miniature tomb boxes out of the blue. Something inspired them. Probably the miniature toys made eons before. The oldest toys ever found in Egypt, miniature toy boats carved from wood, came from a child's tomb dating back 7000 years! So, could it be said the advent of miniatures dates back 7000 years? It could, but consider this: A prehistoric man has learned how to carve a weapon made from wood. While he is out hunting, the prehistoric woman is cleaning the cave and caring for the prehistoric children that are bored to death and making enough noise to attract a hungry saber tooth tiger.  Something must be done to occupy the children before they are all eaten. Prehistoric Dad, using his increasingly larger brain, carves a few miniature birds for the kids after work, and the cave is a quiet and safe place once again. If this was an early Modern Man family, their miniature birds were carved 200,000 years ago. If this family was living during the earliest known period when tools were first used, and children were bored, their miniature birds would be 2.4 million years old! There are not many hobbies today that can make such a claim.

Something must be done to occupy the children before they are all eaten. Prehistoric Dad, using his increasingly larger brain, carves a few miniature birds for the kids after work, and the cave is a quiet and safe place once again. If this was an early Modern Man family, their miniature birds were carved 200,000 years ago. If this family was living during the earliest known period when tools were first used, and children were bored, their miniature birds would be 2.4 million years old! There are not many hobbies today that can make such a claim.

Ancient three-dimensional miniature artifacts exist, yet historians believe no one ever thought to assemble miniatures into a house before the sixteenth century. Egyptian model makers would probably beg to differ. Meketre may not have had a miniature house in his tomb, but what model making father could have resisted his beloved daughter's plea to

" ", or rather, "Make me a little house, too, Daddy?". Unfortunately, any model rooms or houses made for children, or adults were not protected deep inside a rock cliff for 4000 years and have long since vanished, and speculation does not satisfy an historian.

", or rather, "Make me a little house, too, Daddy?". Unfortunately, any model rooms or houses made for children, or adults were not protected deep inside a rock cliff for 4000 years and have long since vanished, and speculation does not satisfy an historian.

One cannot deny the existence of an undeniable and continuing fascination with miniatures since the dawn of man. Artifacts from all over the world can attest to that. Even today, miniature artisans are carving wooden birds, just one-half inch long, using a simple metal blade. Some things have not changed, with the noted exception that miniatures magically became full size in the afterlife. Or has it? Did Meketre's models meet his expectations? You'll have to ask his mummy.

Join us for CDHM's History of Miniatures, Part III, Seeing is Believing

The twenty four Meketre room models were divided equally between the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. If you would like to see more of the Cairo collection, please visit World Visit Guide: Room of the Models. You are in for a treat!

www.worldvisitguide.com/salle/MS00505.html

PART I of our series, The History of Miniatures

Custom Dolls, Houses & Miniatures / CDHM